Architecture should speak of its time and place, but yearn for timelessness.

Frank Gehry

Few would expect it, but Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia, holds a remarkable collection of Art Nouveau architecture, rivaling cities like Prague, Riga, and Budapest, though it lacks the recognition it deserves. How this distinctly European movement made its way to the heart of the Caucasus remains unclear. Some suggest German and Austrian influences, likely transmitted through Russia, along with Georgia’s Black Sea connections that may have helped spread trends. The first Art Nouveau buildings appeared late compared to the rest of Europe, emerging only in the early 1900s.

Visitors strolling through Tbilisi’s less central neighborhoods will notice many of these buildings are crumbling, if not in complete disrepair. Beyond neglect, there seems to be a certain disinterest in this architectural style, likely due to the Soviet occupation beginning in the 1920s. Art Nouveau was seen as frivolous and too closely tied to bourgeois European culture, leading to its swift suppression in favor of more functional and rationalist architecture. This, in turn, explains the academic void of specific studies on the subject in Georgia.

Subscribe to our whatsapp channel!

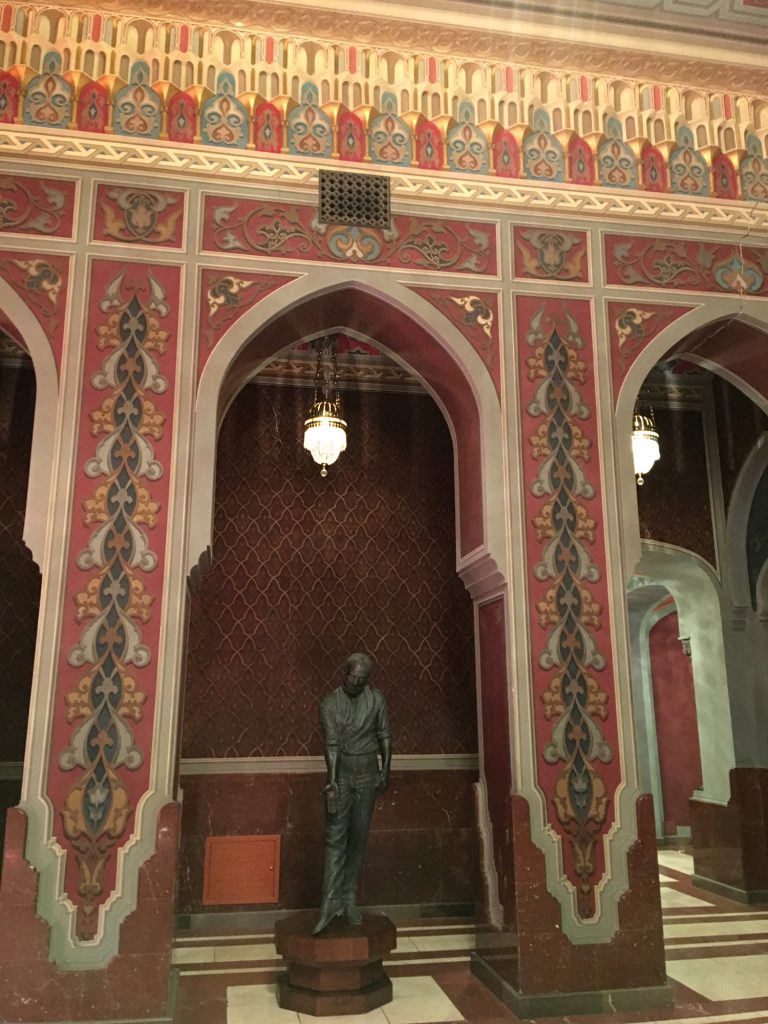

Many buildings are at risk of collapse and might be beyond restoration, potentially facing demolition. A prime example is Tbilisi’s oldest Art Nouveau building on Rome Street, designed by Georgian architect Simon Kldiashvili in 1902. Its wavy balconies and female faces adorning the large windows echo the French floral style, but today it is in a poor state. Better preserved is the grand building at 12 Daniel Chonkadze Street, designed by architect M. Ohajano. Inside are beautiful stained-glass windows reminiscent of the Viennese Secession, though the foundation is giving way on one side, and the interior walls are riddled with large cracks. Only in the last ten years have some of these structures begun to undergo conservation efforts, like the stunning apartment building on Machabeli Street. Designed by Armenian architect G. Sarkesian, the interior features vibrant Hispano-Moorish decorations with Star of David-shaped windows. An intriguing relic on the first-floor landing is a broken mirror, rumored to have cracked when Lavrentiy Beria, Stalin’s notorious right-hand man, gazed into it—never to be repaired since. The most intact and well-preserved Art Nouveau building in Tbilisi is the National Parliamentary Library, built between 1913 and 1916 by architect Anatoly Kalgin. Beyond these exceptions, it is common to encounter sagging floors, broken staircases, and crumbling facades across many buildings, many of which are still inhabited despite never having been restored since their construction. Local preference leans heavily toward modern apartments, and these historic homes are often sold for nominal prices. Fortunately, attitudes have begun to shift in the last decade, and Tbilisi joined the Art Nouveau European Route in 2006.

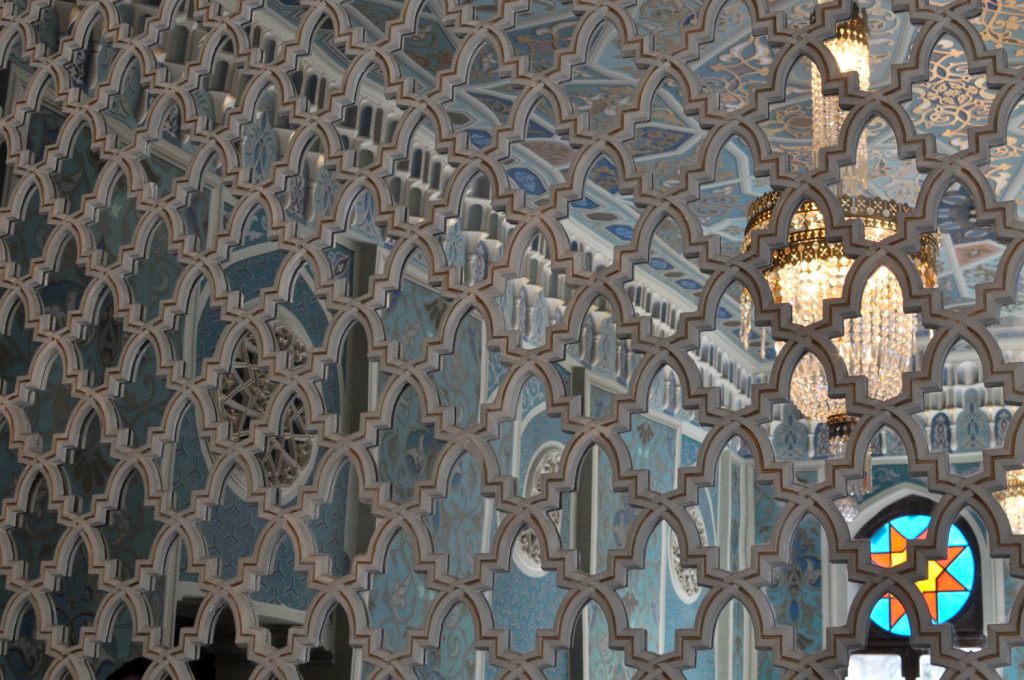

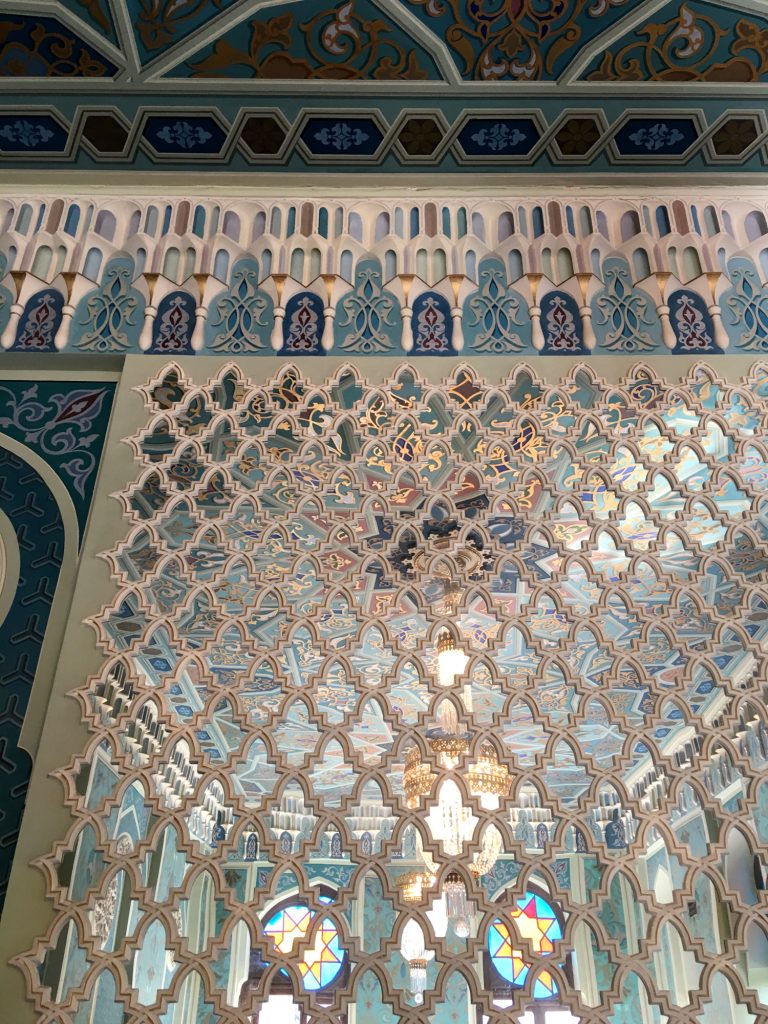

A different story unfolds for the Opera and Ballet Theater on Rustaveli Avenue, the city’s main thoroughfare. This grand Moorish-style building is Georgia’s most important opera house and one of Eastern Europe’s oldest monuments. Originally built in 1848 by Italian architect Scudieri, it could seat 800 people. When Alexandre Dumas visited Tbilisi in 1851, he described it as a “fairy palace,” lauding its delicate and opulent decorations. Sadly, a devastating fire destroyed much of the structure in 1874, and it was rebuilt in 1896 in the Neo-Moorish style by architect Victor Johann Gottlieb Schröter. The theater hosted numerous Russian and Italian performances. Nearly a century later, another fire in 1973 destroyed the interiors once again, along with numerous archival documents, historic costumes, and museum objects. The building’s most recent restoration, completed in 2016 after six years of work, preserved its original style while expanding its spaces. Beyond the three ballet halls, two opera halls, and an orchestra room, the most beautiful are found in the foyer. Here, visitors can ascend a double staircase to the Red Hall and two blue-hued halls adorned with Mudejar-style decorations and mirrored walls with golden frames.

More art nouveau buildings

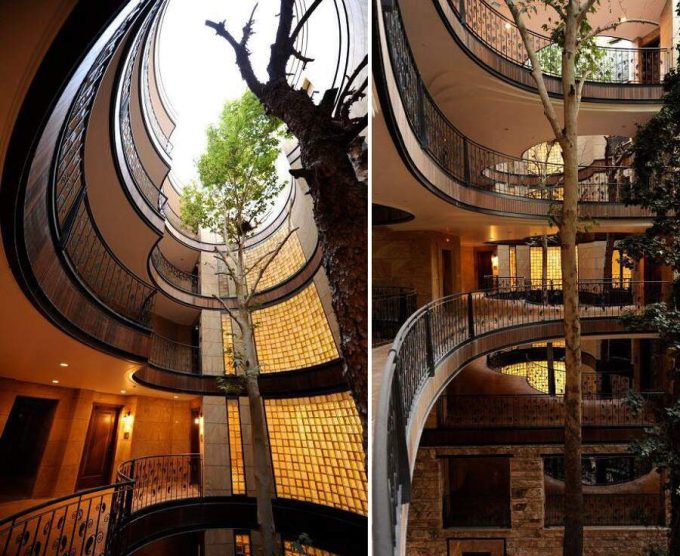

The true gem of Tbilisi’s Art Nouveau is the Writer’s House of Georgia on Machabeli Street. The building, hidden from the street except for its splendid wrought-iron gate, was built between 1903 and 1905 by the wealthy industrialist and brandy producer David Sarajishvili to celebrate his 25th wedding anniversary to Ekaterine Porakishvili. The house immediately became a hub for Tbilisi’s artistic and cultural society, hosting art exhibitions, poetry readings, and traditional Georgian celebrations. Sarajishvili passed away in 1911 without heirs, intending to leave the house for the use of Georgian writers and artists. His wife was eventually forced to sell it at auction, and it was purchased by philanthropist Akaki Khoshtaria, who fulfilled Sarajishvili’s wish, turning the house into a gathering place for intellectuals and artists. Writers such as Paolo Iashvili, Titsian Tabidze, Mikheil Javakhishvii, Pavle Ingorokva, and Konstantine Gamsakhurdia frequented the house, transforming it into a lively intellectual center. Unfortunately, the Soviet occupation, beginning in the 1920s, gradually curtailed this freedom, and by 1937, Khoshtaria had to flee the country. During a critical meeting at the house that same year, Paolo Iashvili, a poet deeply connected to the place, tragically took his life rather than fall into the hands of the Red Army.

Fortunately, the Writer’s House has remained largely intact since its early 20th-century construction, a perfect fusion of European Art Nouveau with Georgian elements such as wooden balconies overlooking the inner garden. Designed by German architect Carl Zaar, with contributions from Tbilisi-based architects Aleksander Ozerov and Korneli Tatishev, the house’s finest room is the grand salon on the first floor. Its exquisite wood paneling was crafted by Georgian woodworker Ilia Mamatsashvili, though the room’s design shows heavy Secessionist influence. Other small, charming rooms, like the green Secessionist room and a more French-inspired space, are also located on the first floor, with access to the elegant Café Littera in the inner garden, one of Tbilisi’s finest restaurants.

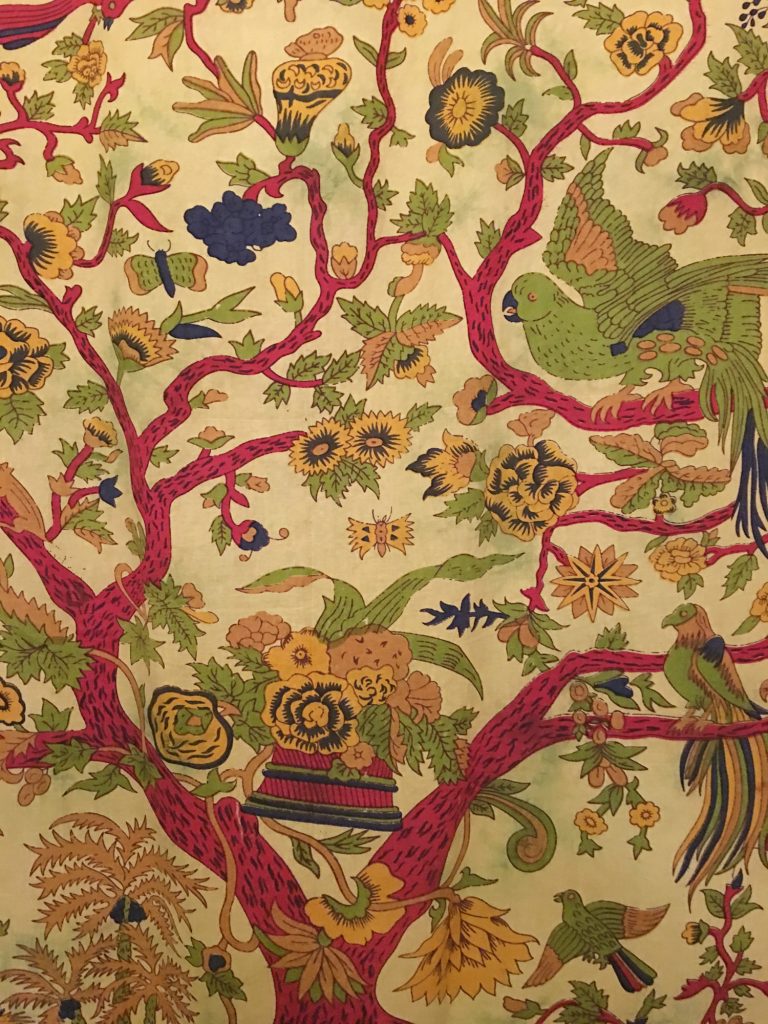

In addition to hosting conferences, exhibitions, lectures, and seminars, the Writer’s House has, since 2017, featured an apartment on its top floor that serves as a hotel, accommodating writers and artists. The apartment, along with the rooms, was designed by Georgian film set designer Guga Kotetishvili, blending Art Nouveau with modern sensibilities and local style. The living room and green corridor are adorned with floral wallpapers and carpets, while the dining room is awash in soft blue hues, ending with a charming bay window overlooking the garden. Each of the five uniquely decorated rooms is dedicated to a poet connected to Georgia in some way: Alexandre Dumas in French style, Nizami Ganjavi in Oriental style, Marjory and Oliver Wardrop in English style, Boris Pasternak in Russian style, and John Steinbeck in American style.

© 2025. All content on this magazine is protected by international copyright laws All images are copyrighted © by Tbilisi Art Nouveau or assignee. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act, the use of any image from this site is prohibited unless prior written permission is obtained. All images used for illustrative purposes only

Author: mediastaff

- architectural decay

- architectural discovery.

- architectural gems

- architectural history

- architectural photography

- architectural preservation

- architectural style

- Art Design

- Art Nouveau

- Caucasus architecture

- cultural heritage

- Design

- European architecture

- Georgian architecture

- hidden architecture

- historical buildings

- neglected architecture

- Photography

- Soviet influence

- Tbilisi Art Nouveau

- Tbilisi travel

- Travel

- travel to Georgia

- urban exploration

Leave a comment