That which is creative must create itself.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

The classical notion of Beauty, as understood through adherence to formal perfection and moral goodness, governed the creative ideals of Neoclassicism. This concept, rooted in the Greek principle of kalokagathía, saw beauty as intertwined with the morally right. Yet, at a certain point, this vision of perfect Beauty was no longer sufficient for expressing aesthetic perfection in art and literature. Why?

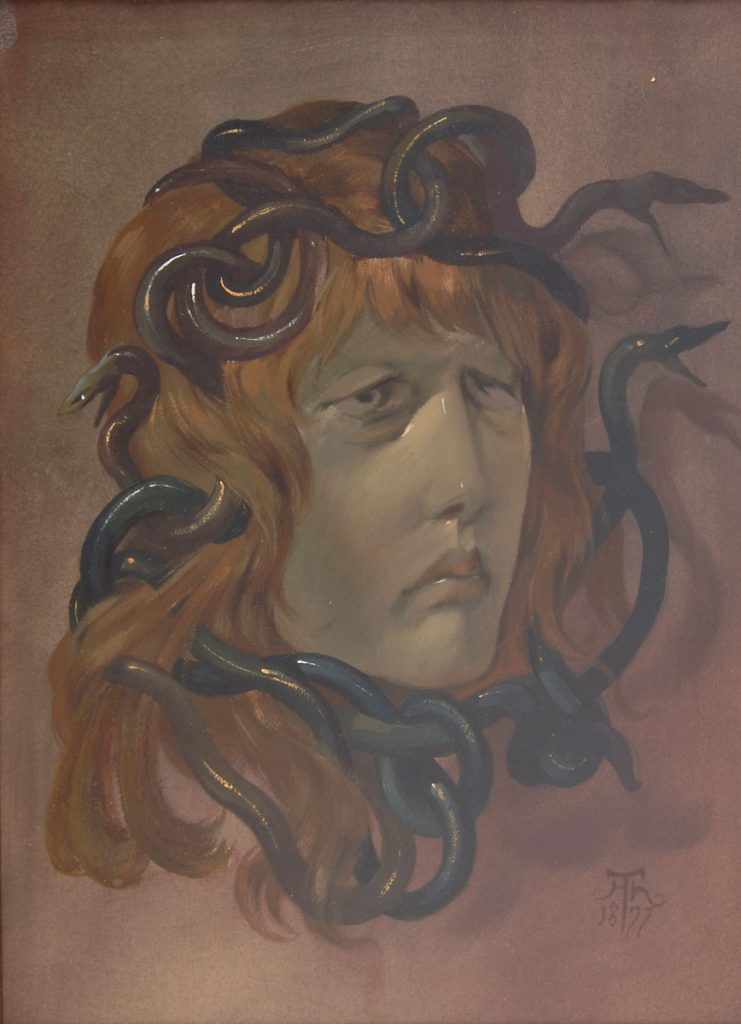

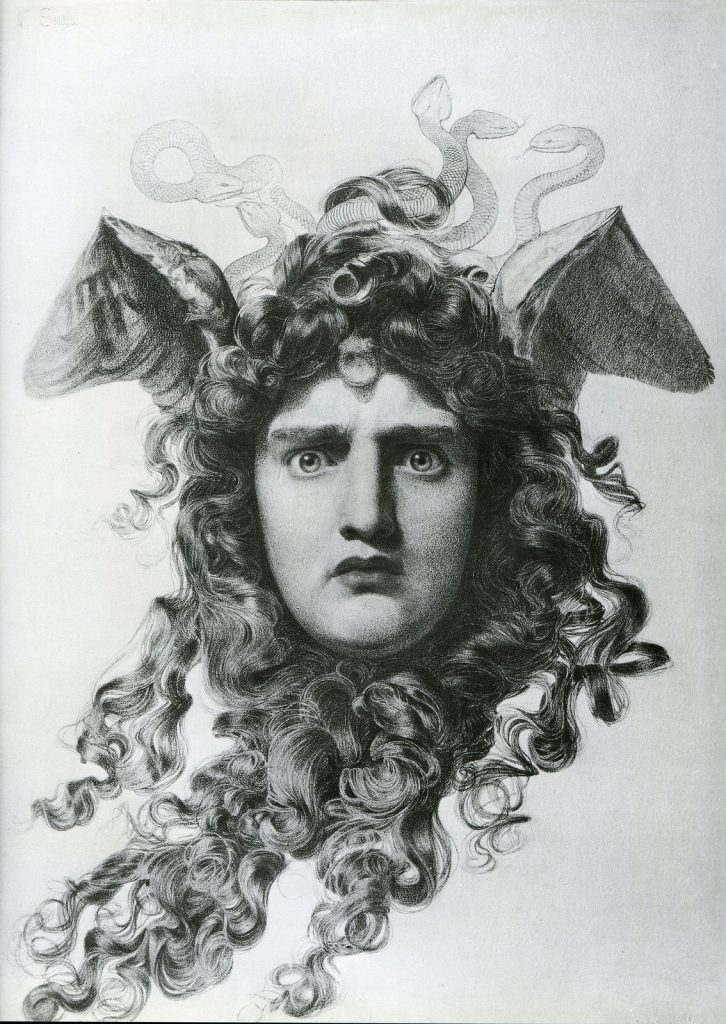

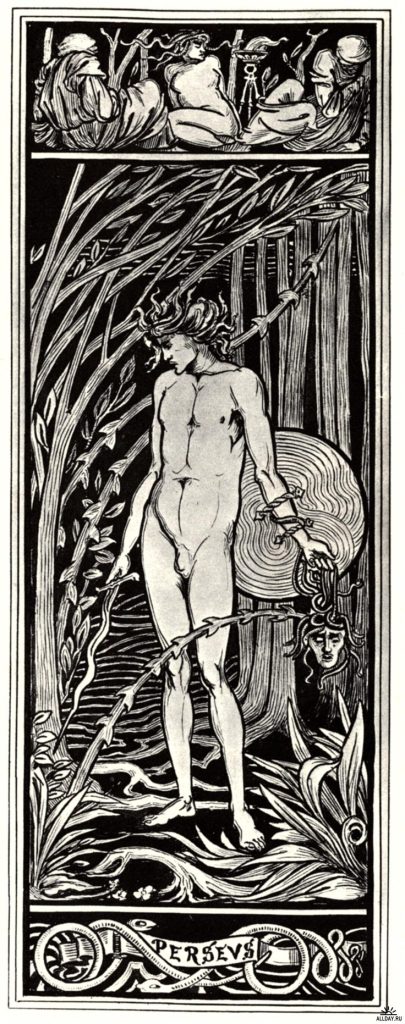

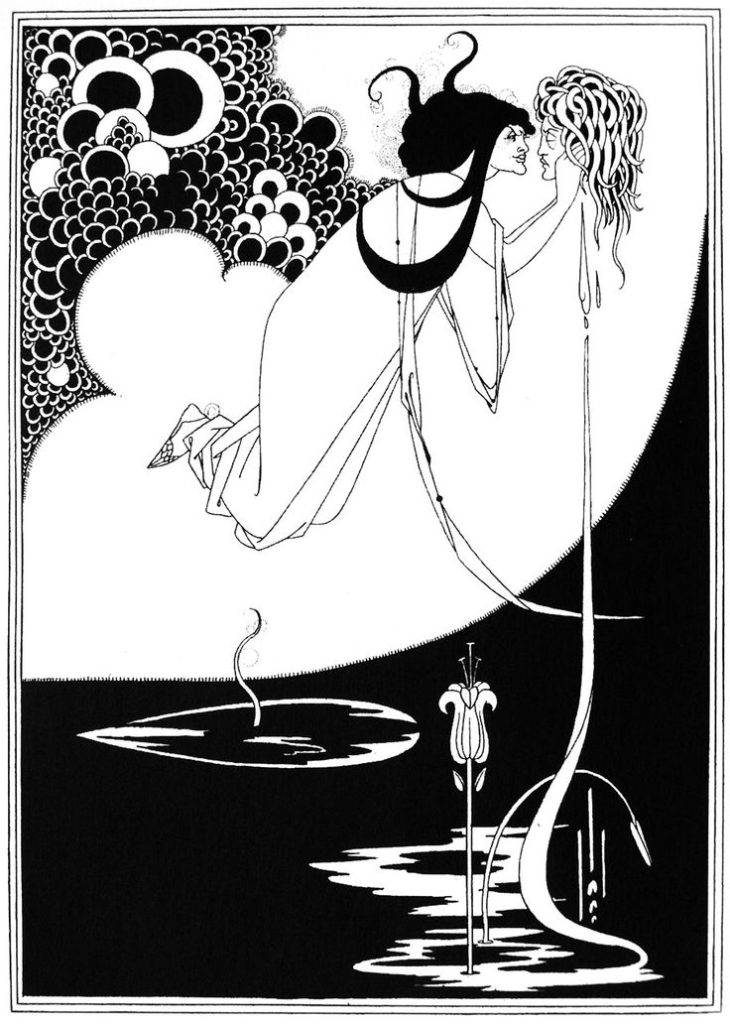

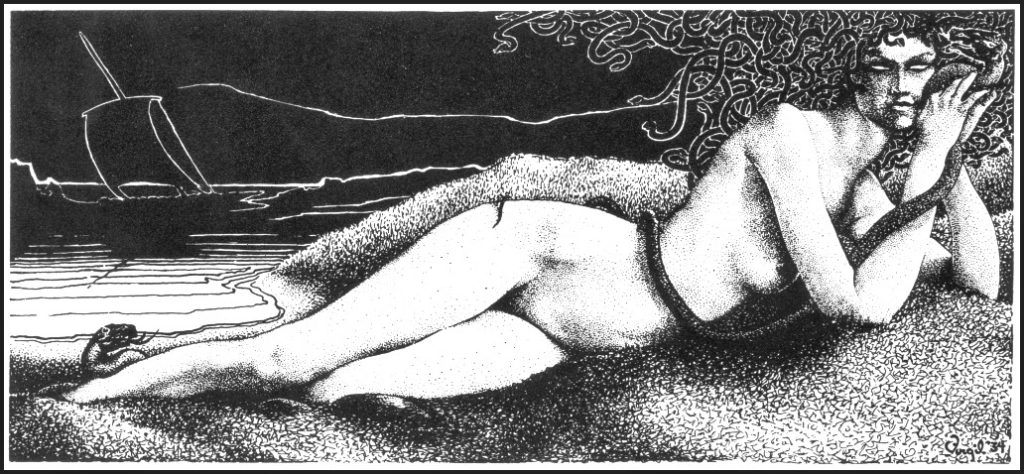

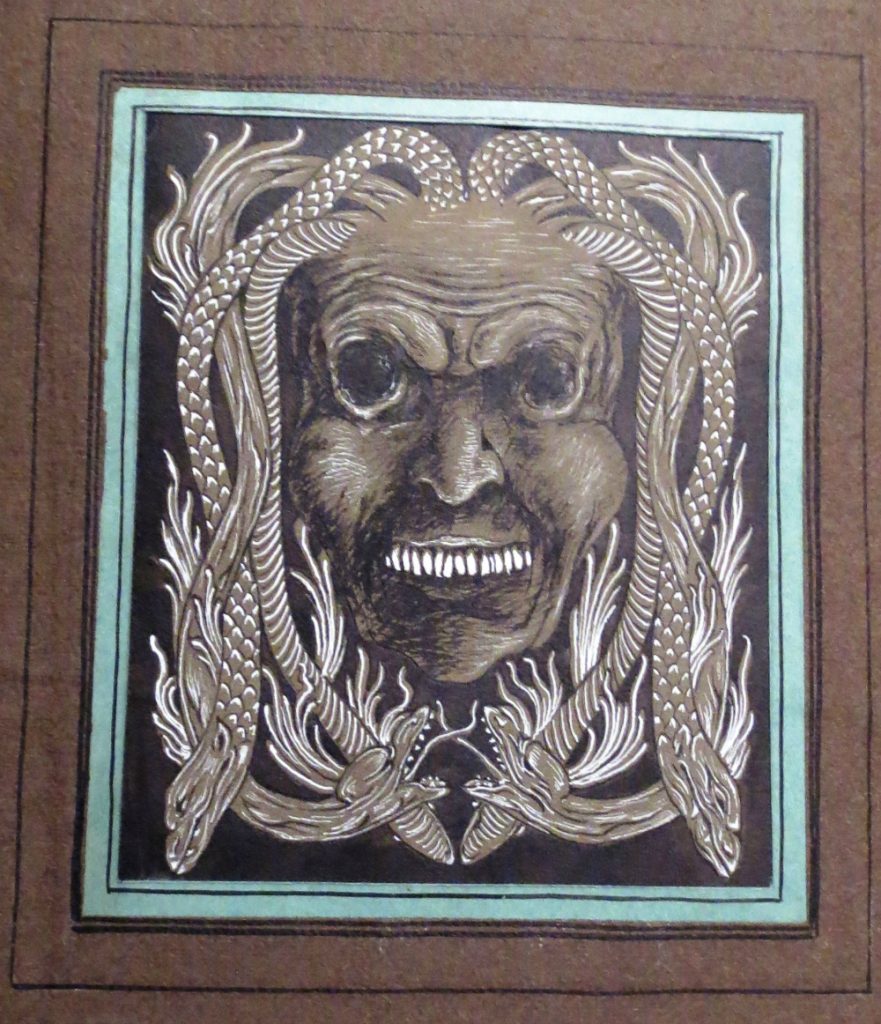

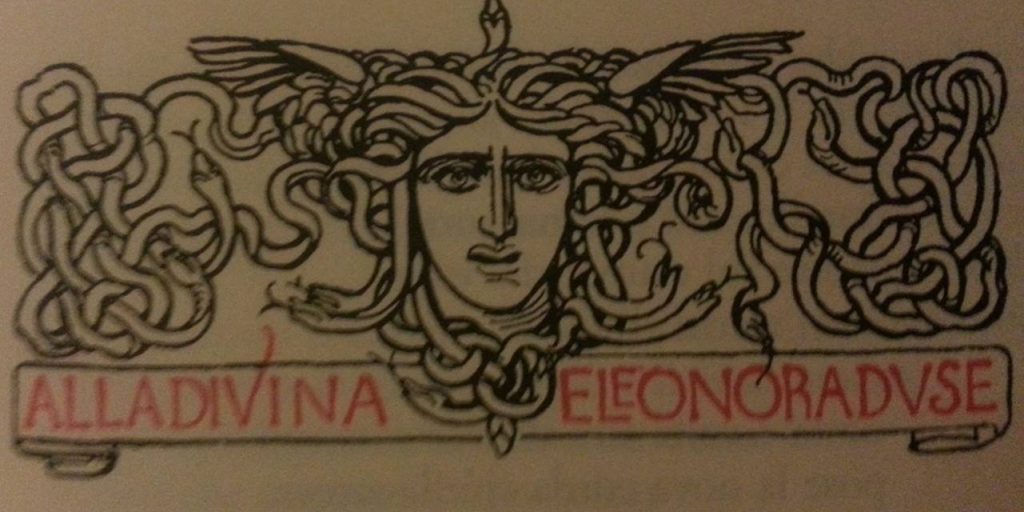

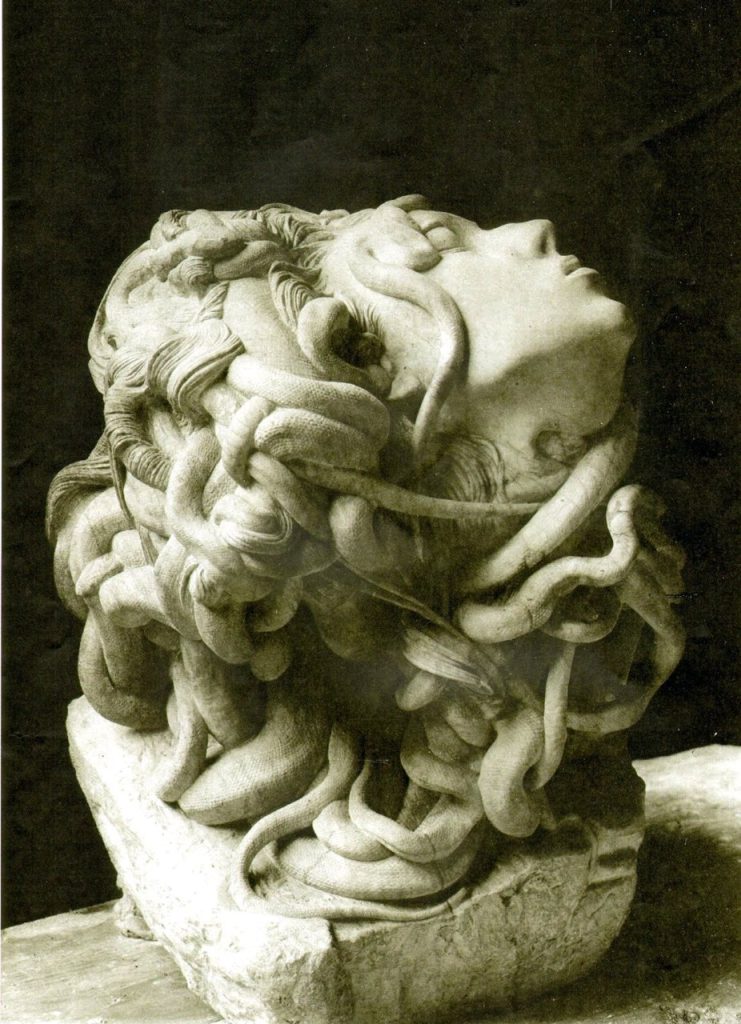

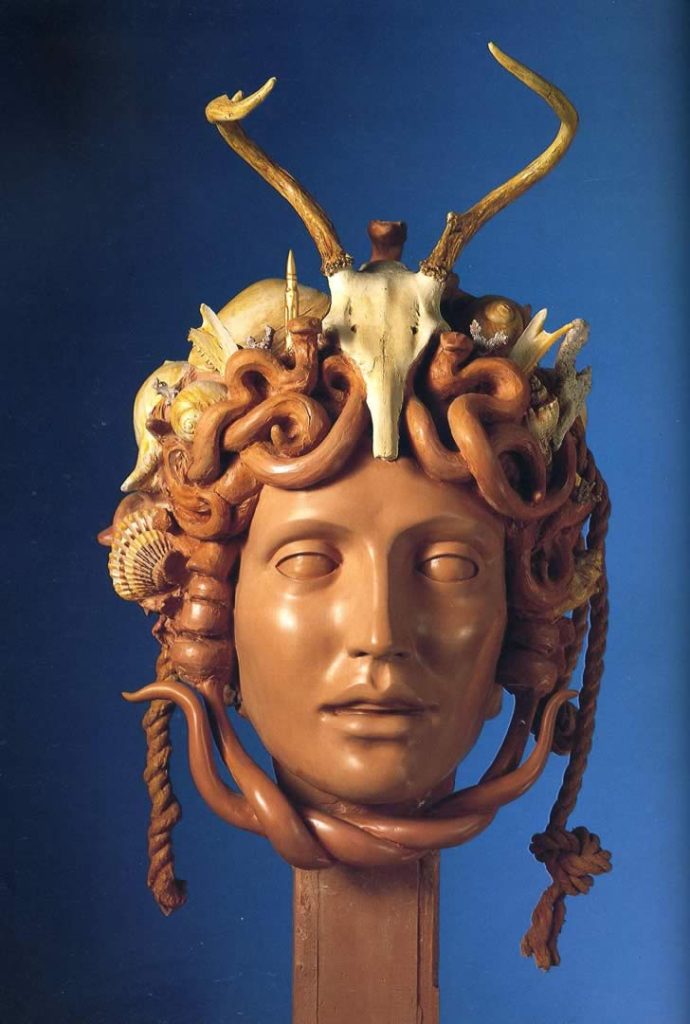

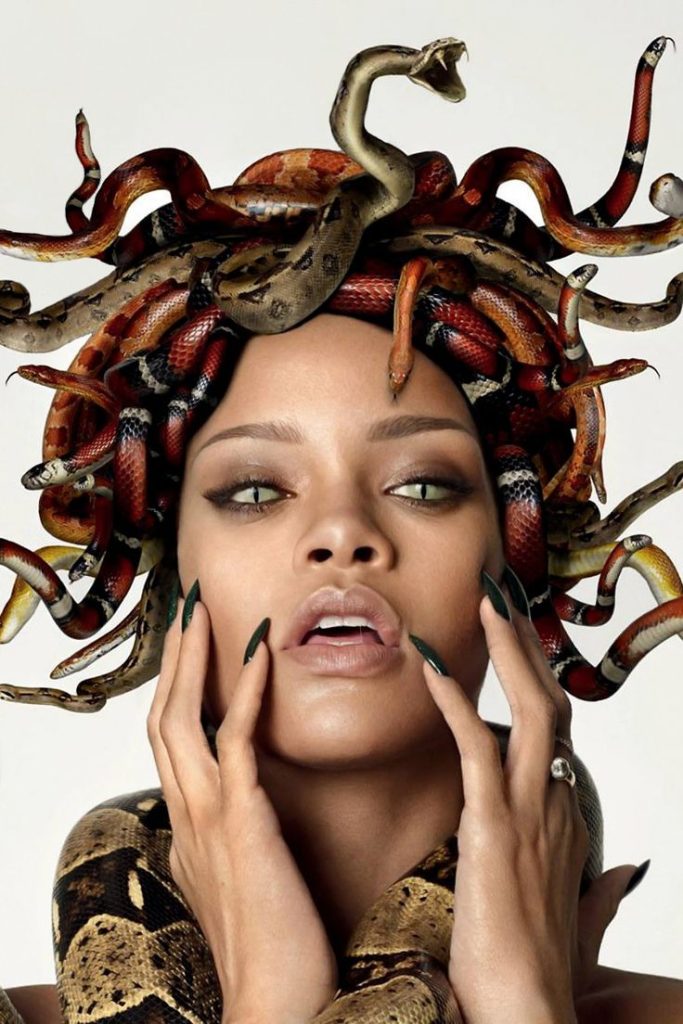

Early Romantic poets, such as Goethe, and later, figures like Percy Bysshe Shelley, began to challenge this idea. Shelley, for instance, found beauty in the terrifying image of the Medusa—an expression of the “tempestuous loveliness of terror.” This marked the Romantic movement’s embrace of the sublime, where beauty was no longer confined to the serene and harmonious but extended to the awe-inspiring and dreadful. Romanticism did not merely discover horror as a source of beauty; it shifted from seeing beauty as an intellectual concept to experiencing it as an emotional and often tragic sensitivity.

Subscribe to our whatsapp channel!

Beauty as Corruption

With Romanticism evolving into Decadence, Charles Baudelaire formalized this new vision of beauty, radically changing its definition. For Baudelaire, Beauty was no longer eternal or perfect but something transient, corruptible, and intertwined with time, fashion, and passion. He argued that Beauty consists of two elements: one eternal and immutable, and the other relative and fleeting. Without the latter, the former would be indigestible to human nature. Thus, Beauty became associated with corruption, impermanence, and the recognition that no longer could modern humanity rely on an eternal, idealized form of Beauty. The modern man understood beauty only as something complex and transitory.

Beauty as Sadness

Baudelaire took this even further, viewing ugliness not as a deviation from the canon but as a realm for innovation. In a world where “everything has been said, everything has been consumed,” the only way to find originality was to explore the shadowy realms of existence. He declared that Beauty is inherently mysterious and melancholic, going so far as to exclude the possibility of a happy Beauty, claiming, “I do not deny that Joy can be associated with Beauty, but it is one of its most vulgar ornaments.”

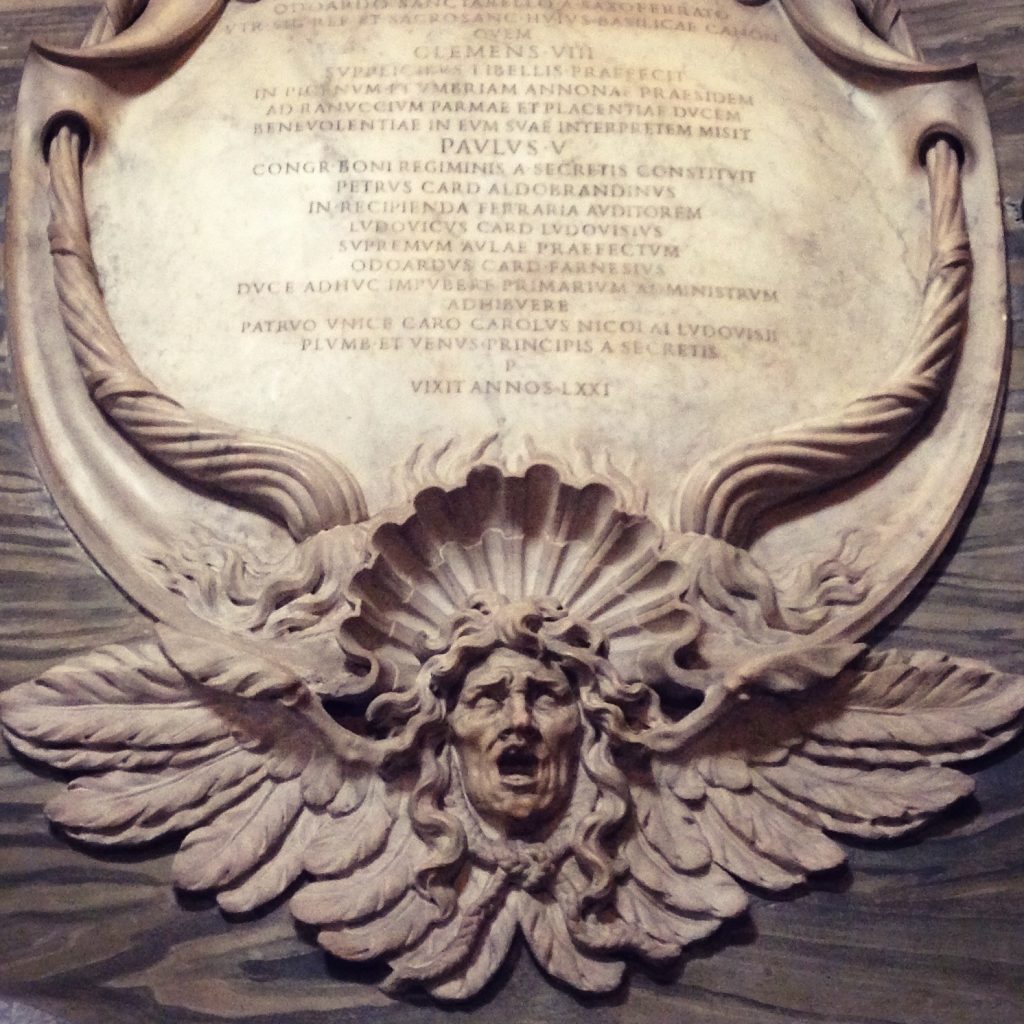

Drawings, illustrations, engravings

For Baudelaire, true Beauty must be tinged with sadness. The concept of Beauty was no longer tied to joy but to melancholy, mystery, and a sense of loss or unfulfilled desire. His vision of a beautiful woman, or a beautiful man, was suffused with an indefinable sadness, a reflection of the struggles, desires, and melancholic longing of the modern soul.

In essence, Baudelaire’s powerful theory of Beauty, defined by melancholy and mystery, shaped the aesthetic ideals of modernity. Beauty became inextricably linked to the tragic and the fleeting, marking a significant departure from the classical pursuit of perfection and eternal form.

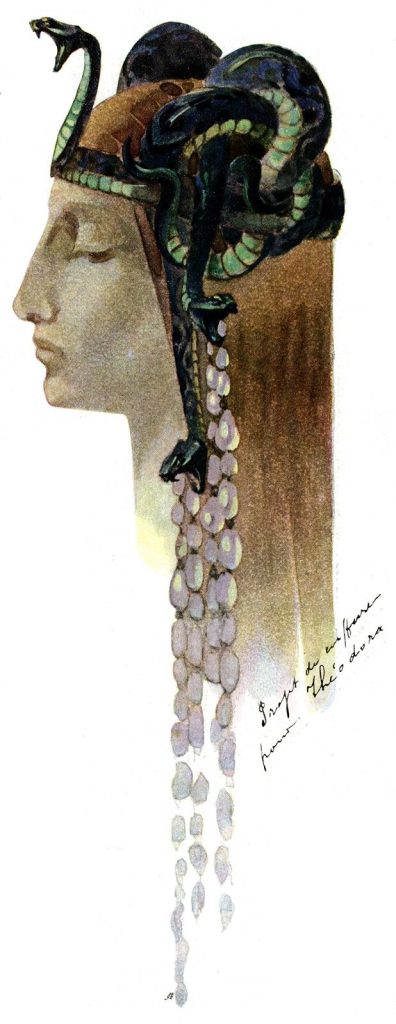

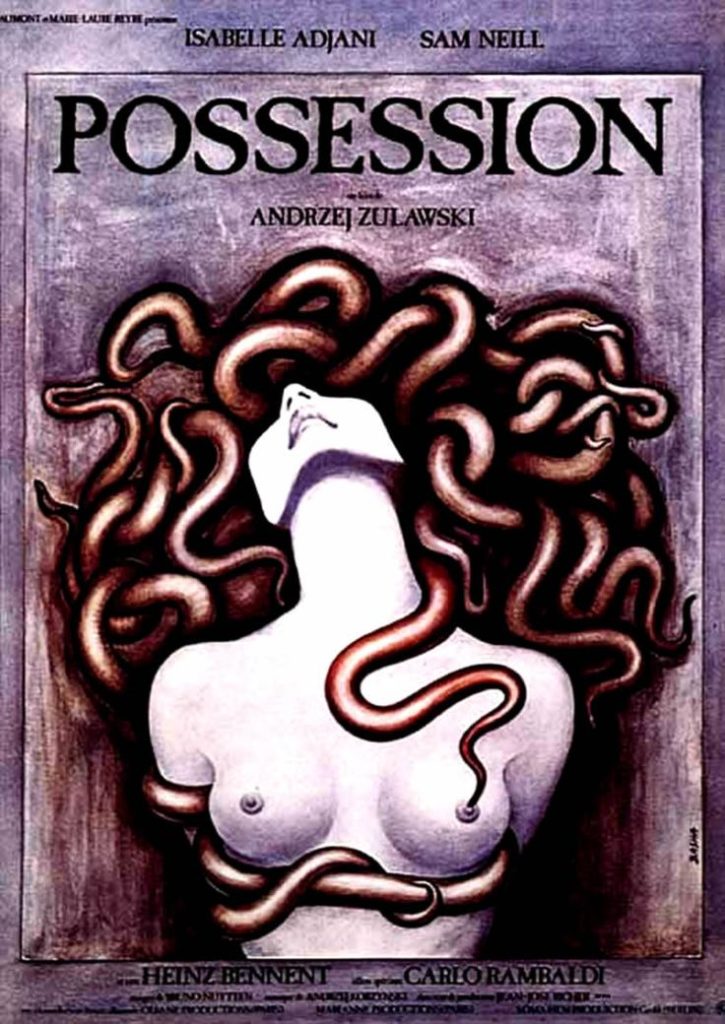

Covers, posters, advertisings, illustrations

Sculptures, jewels

Photography, performers, costumes

© 2025. All content on this magazine is protected by international copyright laws All images are copyrighted © by assignee. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act, the use of any image from this site is prohibited unless prior written permission is obtained. All images used for illustrative purposes only

Author: mediastaff

- aesthetics

- art history

- artistic change

- artistic evolution

- Artistic Expression

- artistic philosophy.

- Artists

- beauty and terror

- beauty in art

- Culture

- Design

- emotional aesthetics

- Goethe

- historical art

- History

- kalokagathía

- literary theory

- Medusa

- Neoclassicism

- Percy Bysshe Shelley

- philosophical aesthetics

- Romantic poetry

- romanticism

- sublime beauty

Leave a comment